Non-Violence vs Politics of Hate: Does Gandhi Still Matter?

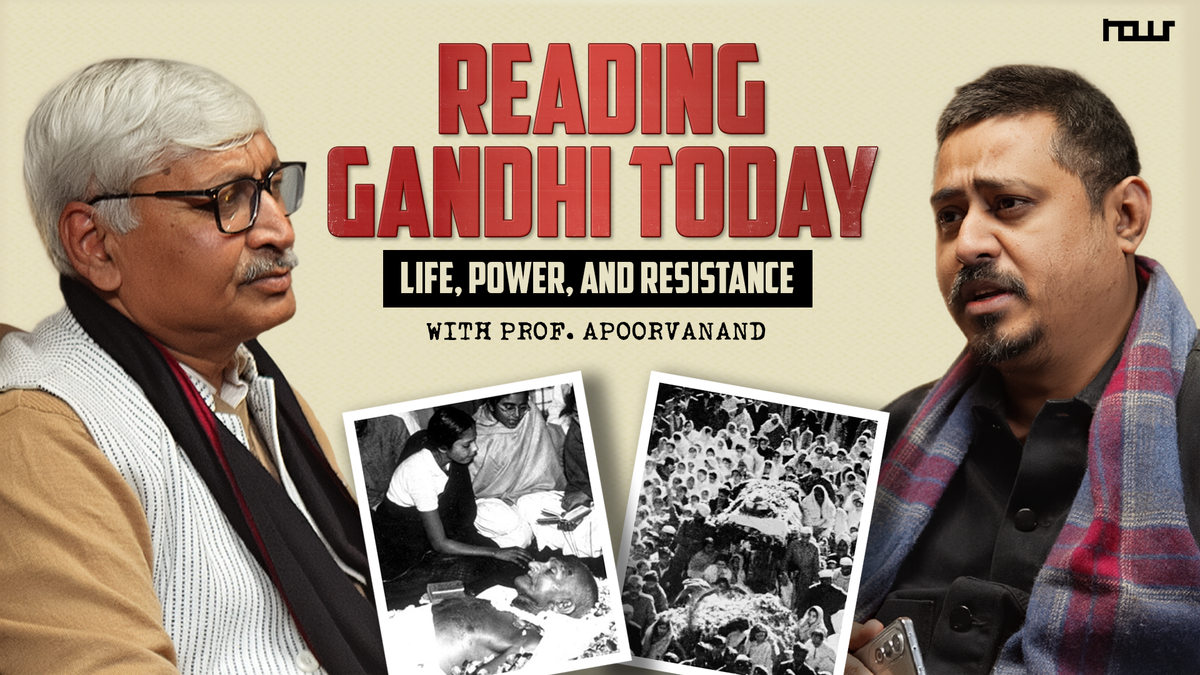

Journalist Asad Ashraf in conversation with Professor Apoorvanand revisits Mahatma Gandhi as a political thinker and moral force. Moving beyond hagiography, the discussion examines his ideas on non-violence, mass politics, economics, and why Gandhi continues to unsettle contemporary India.

The Radical Relevance of Gandhi: Non-Violence, the State, and the Politics of Hate

Each year, Mahatma Gandhi is ritually remembered—his image invoked, his words selectively quoted, his legacy safely contained within statues, currency notes, and commemorative speeches. Yet Gandhi was never meant to be comfortable. His life and thought were not designed to reassure power but to unsettle it. In a conversation marking the anniversary of his assassination, Professor Apoorvanand revisits Gandhi not as a national icon but as a deeply radical political thinker whose ideas remain profoundly disruptive to contemporary India.

The discussion moves beyond familiar moral abstractions to ask difficult questions: What did non-violence actually mean as a political method? Why did Gandhi’s ideas provoke hostility not only from colonial rulers but from within Indian society itself? And why does Gandhi continue to be an uncomfortable presence in a nation increasingly shaped by majoritarian politics, economic excess, and the normalization of hate?

Becoming Gandhi: Politics Forged Through Experience

Gandhi was not born a political visionary. His politics were shaped slowly, through dislocation, humiliation, learning, and ethical struggle. His formative years in London are often reduced to anecdotes about diet and discipline, but they were crucial in expanding his moral imagination. There, Gandhi encountered people who did not share his religion, nationality, or culture yet treated him as an equal. This experience quietly dismantled the assumption that society must be organized along rigid religious or civilizational lines.

It was also in this period that Gandhi began engaging deeply with texts across traditions—the Gita, Christian theology, and Islamic ethics—often at the suggestion of non-Hindus. Religion, for Gandhi, was never a closed inheritance; it was an ongoing dialogue.

The decisive transformation, however, occurred in South Africa. There, Gandhi confronted racism not as an abstract injustice but as a lived reality. Thrown out of a train compartment, denied dignity, and treated as expendable, he was forced to confront what it meant to be classified as lesser. Importantly, his awakening was collective rather than individual. Muslim traders and fellow migrants explained to him that indignities such as being asked to remove his turban were not trivial inconveniences but assaults on self-respect.

Initially, Gandhi’s struggle was limited—focused on rights for Indians. But over time, it expanded into a broader resistance to inequality itself. South Africa taught Gandhi a foundational political lesson: liberation cannot be achieved in isolation. Justice requires solidarity across racial, religious, and social boundaries.

Non-Violence as Political Strategy, Not Moral Ornament

One of the most enduring misunderstandings of Gandhi is the belief that non-violence was merely a spiritual or moral preference. As Professor Apoorvanand explains, Gandhi’s commitment to ahimsa and satyagraha was profoundly political and deeply pragmatic.

Before Gandhi, the dominant assumption was that tyranny could only be confronted through violence. Armed struggle, however, concentrates power in the hands of a few—those who possess weapons, physical strength, and access to secrecy. Such movements inevitably exclude the majority.

Non-violence inverted this logic. By rejecting violence, Gandhi transformed the freedom struggle into a genuinely mass movement. Women, the elderly, the poor, and the unarmed could all participate. Courage was no longer measured by one’s ability to kill, but by one’s willingness to shed fear.

Gandhi’s non-violence was also interfaith at its core. His understanding of fraternity drew from Islamic ethics, while his emphasis on love and service resonated with Christian traditions. Far from being narrowly Hindu, Gandhian politics was forged through a serious engagement with multiple faiths. Without this plural moral grounding, non-violence could not have functioned as a universal political language.

Gandhi and Ambedkar: Conflict, Caste, and Political Limits

Any serious engagement with Gandhi must confront his fraught relationship with B.R. Ambedkar. The disagreement was not merely tactical; it reflected fundamentally different diagnoses of caste.

Gandhi believed caste could be morally reformed from within Hindu society. Strategically, he focused on attacking untouchability—the most indefensible aspect of the system—hoping it would destabilize caste hierarchy as a whole. Ambedkar, by contrast, saw caste as structurally and theologically entrenched. For him, reform was insufficient; annihilation was necessary.

Professor Apoorvanand resists simplistic judgments. While Gandhi’s insistence on retaining Dalits within Hinduism is rightly criticized, the Poona Pact cannot be dismissed outright as a political failure. It did increase representation and political leverage for depressed classes within the colonial framework.

However, on the question of the village, Apoorvanand aligns decisively with Ambedkar. Gandhi’s romanticization of the village as a harmonious republic ignored its brutal realities. Indian villages have historically been spaces of segregation, enforced hierarchy, and routine violence. The apparent “peace” of village life often exists only because resistance has been crushed or deferred. Ambedkar’s description of the village as a site of ignorance and oppression remains disturbingly accurate.

Economics Beyond Greed: The Human Measure

Gandhi’s critique of modern economics appears almost prophetic today. At the heart of his economic thought was the idea of the human measure—that production, consumption, and speed must remain tethered to human dignity and ecological balance.

Gandhi warned that an economy driven by endless growth would alienate workers from their labor and humanity from nature. What he anticipated was not merely inequality, but environmental catastrophe and moral exhaustion. In an age of climate crisis and hyper-consumption, his warnings read less like idealism and more like foresight.

The contrast with Nehru is often overstated. Professor Apoorvanand suggests that Nehru, constrained by the immediate responsibility of feeding a newly independent and impoverished nation, operated as the “last Gandhian” in spirit. He relied on scientific planning not out of faith in unchecked industrialism, but out of necessity. Where Gandhi trusted moral intuition, Nehru was forced to rely on state machinery to avert famine.

Religion, Secularism, and the Protection of Minorities

Perhaps Gandhi’s most urgent relevance today lies in his understanding of religion and the state. Gandhi was openly religious—he described himself as a Sanatani Hindu—but he rejected any attempt by the state to define or regulate faith.

For Gandhi, secularism did not mean the absence of religion. It meant the refusal of the state to impose a singular religious identity. The moment the state claims ownership over religion—by defining who Rama belongs to, or what Hinduism must look like—it destroys religious plurality and democratic freedom alike.

This is why Gandhi consistently positioned himself as a defender of minorities. He fasted for Muslims not out of favoritism, but because democracy, in his view, is judged by how it treats the vulnerable. His assertion was simple and radical: he would be “pro-Muslim” in India because Muslims were the minority, just as he would be “pro-Hindu” in Pakistan.

Martyrdom: Standing Against One’s Own

Gandhi’s assassination was not an accident of history. By the final years of his life, Gandhi was no longer confronting British power; he was confronting the moral collapse of his own society. In Noakhali and Delhi, he stood alone against communal mobs, urging Hindus and Sikhs not to surrender to cowardice and bloodlust.

This was his greatest act of courage—standing against the majoritarian impulse of his own community. For those invested in the idea of a Hindu Rashtra, Gandhi represented an insurmountable obstacle. His murder was the culmination of an ideology that viewed empathy as betrayal and restraint as weakness. That ideology did not die with him.

Conclusion: Remembering Gandhi Without Neutralizing Him

Independent India has often neutralized Gandhi by reducing him to symbolism—invoked for cleanliness drives, national rituals, and moral platitudes. In doing so, it has stripped him of his most radical quality: his refusal to compromise with injustice, even when it came from “his own.”

As Professor Apoorvanand observes, India has struggled to produce leaders with Gandhi’s moral clarity since Nehru. Compromises with communal power have become routine, and courage has been replaced by calculation.

To remember Gandhi today is not to sanctify him, but to inherit his discomfort. It is to defend minorities when it is unpopular, to resist the fusion of state and religion, to question an economy built on excess, and to refuse the politics of hate—even when it speaks in the language of one’s own community.

That, more than any statue or slogan, is Gandhi’s unfinished demand.

Support Independent Media That Matters

Nous is committed to producing bold, research-driven content that challenges dominant narratives and sparks critical thinking. Our work is powered by a small, dedicated team — and by people like you.

If you value independent storytelling and fresh perspectives, consider supporting us.

Contribute monthly or make a one-time donation.

Your support makes this work possible.