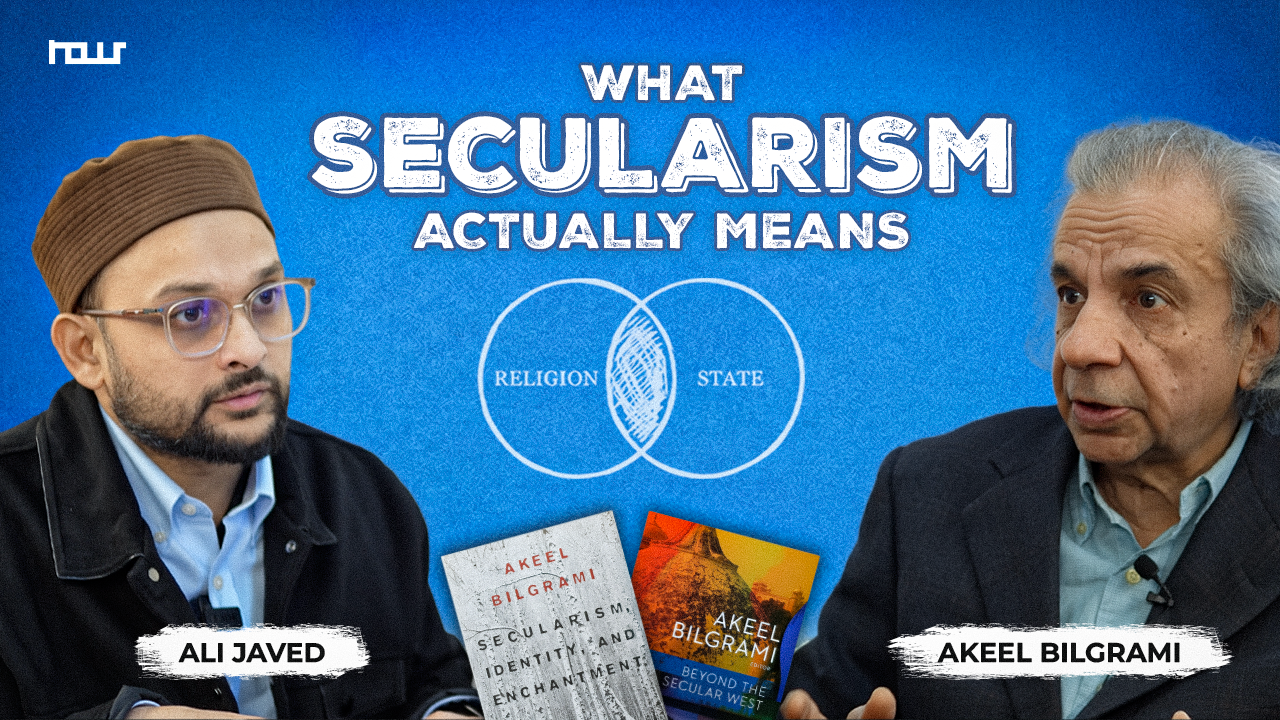

Why Gandhi Thought India Didn’t Need Secularism | Prof. Akeel Bilgrami

Prof. Akeel Bilgrami unpacks the meaning of secularism, distinguishing it from secularisation and tracing its historical evolution. The conversation explores Gandhi’s critique, Mughal governance, and contemporary political challenges shaping the future of secularism in India.

In contemporary political debates, secularism is often misunderstood — frequently conflated with secularisation or assumed to mean the decline of religion itself. But are these really the same? What does secularism actually mean, and how has the concept evolved within different historical and political contexts?

In this conversation, Professor Akeel Bilgrami joins Ali Javed to explore the conceptual, historical, and political dimensions of secularism. The discussion examines the distinction between secularisation as a social process and secularism as a political doctrine, tracing the European origins of secularism and engaging with Gandhi’s argument that India’s historical conditions did not necessitate secularism in the same form. The conversation also reflects on Mughal governance and debates around secularisation in Indian history, contemporary Hindutva critiques of secularism, and the ongoing crisis and future possibilities of secularism in India today.

Beyond Neutrality: Reimagining Secularism in India

In contemporary India, secularism has become a strangely embattled word. It is dismissed as elitist, derided as pseudo, or rejected as a European transplant unsuited to the subcontinent’s civilizational depth. Against this tide, philosopher Akeel Bilgrami offers a strikingly rigorous and morally urgent defense—not of a tired slogan, but of a reimagined political doctrine capable of meeting India’s present crisis.

Drawing from constitutional theory, intellectual history, and the moral philosophy of Mahatma Gandhi, Bilgrami argues that secularism in India has been conceptually misunderstood and politically diluted. What we need, he insists, is not a vague commitment to “neutrality,” but a principled ordering of values—a structure that can withstand majoritarian pressure while protecting both religious freedom and constitutional rights.

The Problem with “Neutrality”

For decades, Indian secularism has been described as the state maintaining equal distance from all religions—a formulation often associated with thinkers like Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan and, in contemporary liberal discourse, Amartya Sen. This “equidistance” model appears fair on the surface. But Bilgrami argues that it is philosophically thin and politically inadequate.

Neutrality, as commonly invoked, lacks operational clarity. What does it mean for a state to be neutral when religious practices conflict with constitutional guarantees? Can neutrality adjudicate between a demand to ban a book deemed blasphemous and the constitutional protection of free speech? Can it address conflicts between personal laws and gender equality?

Bilgrami’s answer is no. Neutrality, in this sense, is an aspiration, not a doctrine. It provides no rule of priority when values collide.

Lexicographical Ordering: A Stronger Doctrine

To replace this vagueness, Bilgrami proposes what he calls a “lexicographical ordering” of principles—a term borrowed from logic and mathematics. In a dictionary, entries follow a strict sequence; similarly, in a secular polity, principles must follow a strict hierarchy.

He identifies three components:

- Freedom of religion — the right to believe, worship, and practice.

- Constitutional principles — free speech, equality before law, gender justice, democratic rights.

- Secularism as ordering rule — a doctrine that establishes priority between the first two.

Under this framework, when religious practices clash with constitutional principles, constitutional rights must prevail. Not because religion is inferior, but because the political community is constituted by shared civic commitments, not theological doctrines.

This principle must apply universally. If a Hindu group demands censorship in the name of religious hurt, free speech prevails. If Muslim groups demand banning a novel such as The Satanic Verses, free speech still prevails. Secularism, in this sense, is not balancing religions against each other—it is being consistent in upholding constitutional primacy.

This is a far more demanding vision than “equal respect.” It requires the state to withstand popular sentiment when sentiment undermines fundamental rights.

Europe’s Damage, India’s Illusion

Bilgrami situates secularism historically. In Europe, secularism emerged as a corrective to religious wars and majoritarian nationalism following the Peace of Westphalia. As European nations consolidated, they often defined themselves by excluding internal minorities—Jews, Catholics, or other “outsiders.” Secularism was invented as a repair mechanism to disentangle religious identity from state power.

Gandhi believed India did not require such a repair. He spoke of India’s “unselfconscious pluralism”—a civilizational habit of coexistence that did not depend on formal separation between religion and politics. For Gandhi, secularism seemed like a European solution to a European pathology.

But here Bilgrami introduces a profound inversion: if Gandhi were alive today, the very reason he rejected secularism then would compel him to embrace it now.

Since the late 20th century, India has witnessed the rise of majoritarian nationalism reminiscent of European patterns. Religious identity is increasingly used to define the nation, and minorities are cast as suspect or external to the national core. The “damage” that secularism was designed to repair has, arguably, arrived.

In such a context, secularism is no longer an imported abstraction. It becomes a necessary defense mechanism.

Secularism Is Not Secularization

Public debates often conflate secularism with secularization. Bilgrami insists on their difference.

- Secularization is a sociological process—decline in religious belief or ritual participation.

- Secularism is a political doctrine regulating the state’s relationship to religion.

India does not require enforced secularization of the sort seen in the Soviet Union or under Mustafa Kemal Ataturk. The state need not homogenize dress, ritual, or dietary practice. Religious life can flourish—so long as it does not violate constitutional commitments.

This distinction is critical. Secularism, properly understood, is not hostility to religion. It is the architecture of coexistence in a rights-based polity.

The Shaheen Bagh Moment

Bilgrami sees in the anti-CAA protests—particularly at Shaheen Bagh—a rare political synthesis.

Unlike a purely Nehruvian appeal to abstract constitutionalism, or a purely Gandhian invocation of moral pluralism, the protesters combined both. They invoked poetry, shared cultural memory, and India’s plural past—while firmly grounding their demands in constitutional guarantees.

This fusion was unprecedented. It demonstrated that constitutionalism need not be culturally rootless, and that tradition need not be anti-modern. The protests challenged the narrative that secularism is alien to Indian soil by showing how deeply constitutional rights resonate within lived pluralism.

In that moment, secularism was not a Western doctrine. It was a lived Indian practice.

Caste, Capitalism, and the Federal Question

Bilgrami also reflects on caste politics and neoliberal transformation. The democratizing energies unleashed by Mandal politics expanded representation. Yet, under market-driven governance, caste identities often become instruments in a competitive “culture of benefits.”

Here lies a paradox. The aspiration of B. R. Ambedkar was the annihilation of caste. Yet access to state resources frequently requires the preservation of caste identity. Justice demands recognition; equality demands transcendence. Secular constitutionalism must navigate this tension without entrenching hierarchy.

Federalism presents another axis of possibility. Bilgrami suggests that strong federal structures could temper homogenizing nationalism. Cultural and religious traditions in southern India differ markedly from northern political mobilizations. A robust federalism may preserve plural democratic energies against centralized majoritarianism.

A Secularism of Courage

The deeper insight in Bilgrami’s intervention is that secularism is not merely institutional—it is moral. It requires courage from the state and from citizens. It asks a majority to accept limits on its cultural dominance. It asks minorities to trust constitutional guarantees over communal mobilization. It demands consistency even when consistency is unpopular.

In a climate where constitutional language is sometimes dismissed as elite rhetoric, Bilgrami reminds us that rights are the only vocabulary capable of protecting both believer and dissenter.

Secularism, reimagined as lexicographical ordering, does not diminish religion. It protects religion from being weaponized by power. It ensures that faith remains a matter of conscience rather than coercion.

Repairing the Present

India stands at a crossroads. The choice is not between Westernization and tradition. It is between majoritarian nationalism and constitutional democracy.

Bilgrami’s argument reframes the debate: secularism is not a relic of postcolonial idealism. It is a necessary repair in an age where nationalism risks hollowing out citizenship. If European history taught the world the dangers of fusing religion with nationhood, India’s present moment underscores the urgency of learning that lesson afresh.

To move beyond neutrality is to accept that democracy requires ordered priorities. Freedom of religion matters. But when it collides with equality, dignity, or free speech, a republic must know which value comes first.

Secularism, in this deeper sense, is not about distancing the state from religion. It is about protecting the moral architecture of citizenship itself.

And in that task, it may be more Indian—and more urgent—than ever before.

Support Independent Media That Matters

Nous is committed to producing bold, research-driven content that challenges dominant narratives and sparks critical thinking. Our work is powered by a small, dedicated team — and by people like you.

If you value independent storytelling and fresh perspectives, consider supporting us.

Contribute monthly or make a one-time donation.

Your support makes this work possible.