Muslims, Development, and the Politics of Neglect in Bihar

Despite forming 17% of Bihar’s population, Muslims remain largely invisible in its development story. Concentrated in Seemanchal’s poorest districts, they face deep gaps in education, jobs, and representation—raising urgent questions ahead of the 2025 Bihar election.

Invisible Bihar: The Untold Story of Muslims in Seemanchal | Poverty, Politics & Representation

Introduction

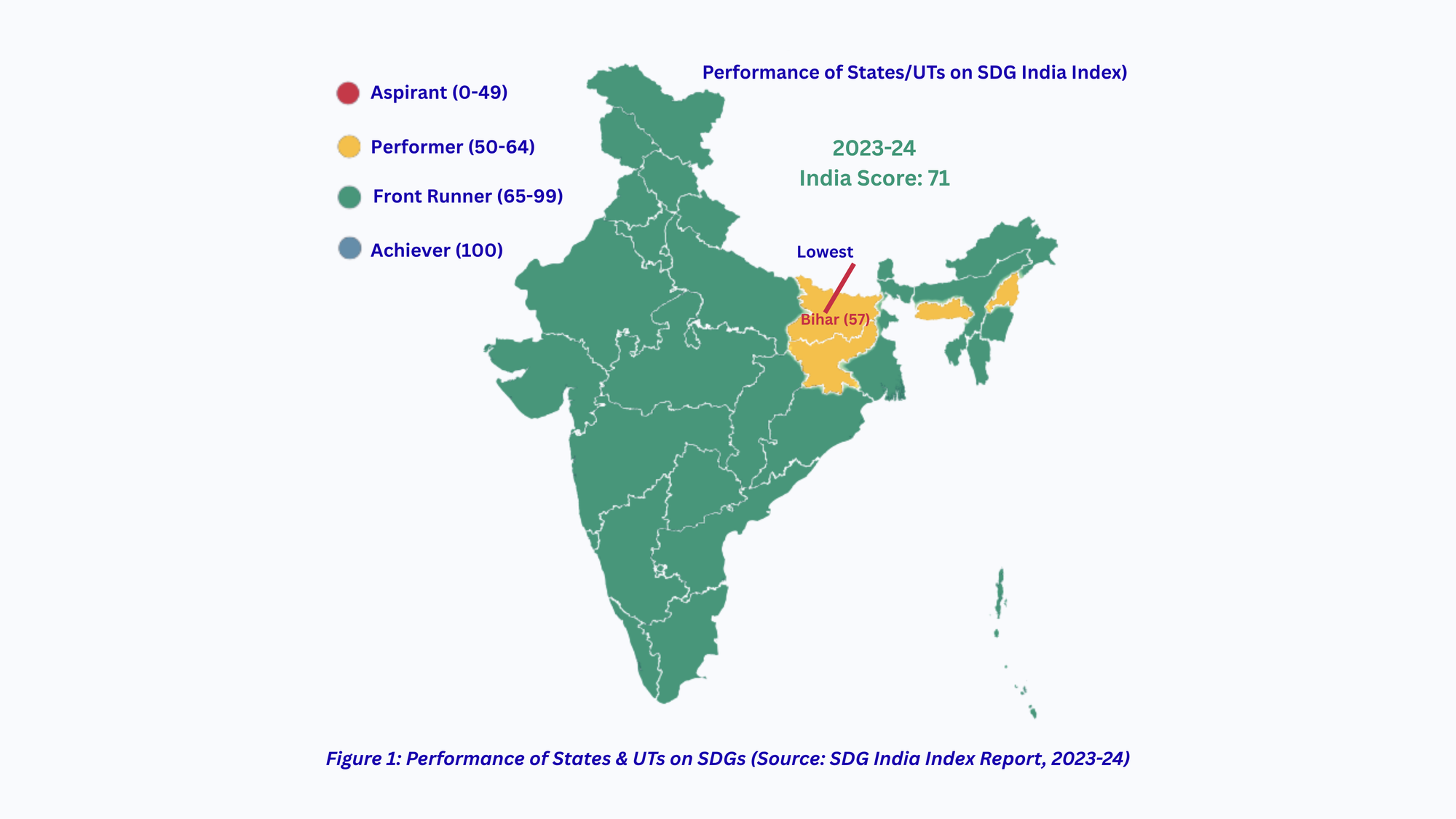

Bihar is India’s third most populous state. Yet, despite its size and historic legacy, it remains one of the least developed regions in the country. Poverty, unemployment, large-scale migration, and poor infrastructure continue to shape the everyday lives of millions here.

Amid these broader challenges lies a story even less acknowledged — the story of Bihar’s Muslims. With the 18th Bihar Vidhan Sabha elections of 2025 around the corner, it becomes crucial to ask: what does the development agenda look like this time? More importantly, does this agenda include Muslims? Are their concerns represented, or will they once again be reduced to a mere vote bank without genuine empowerment?

This article examines the social, economic, and political condition of Muslims in Bihar — particularly in the Seemanchal region, one of the most backward areas in the state. It highlights how development, governance, and politics have consistently overlooked this community, leaving them at the margins of progress.

Bihar’s Muslim Population: A Snapshot

Bihar’s population stands at roughly 10.4 crore, of which more than 1.7 crore are Muslims — around one out of every six residents. This makes Bihar the state with the third-largest Muslim population in India.

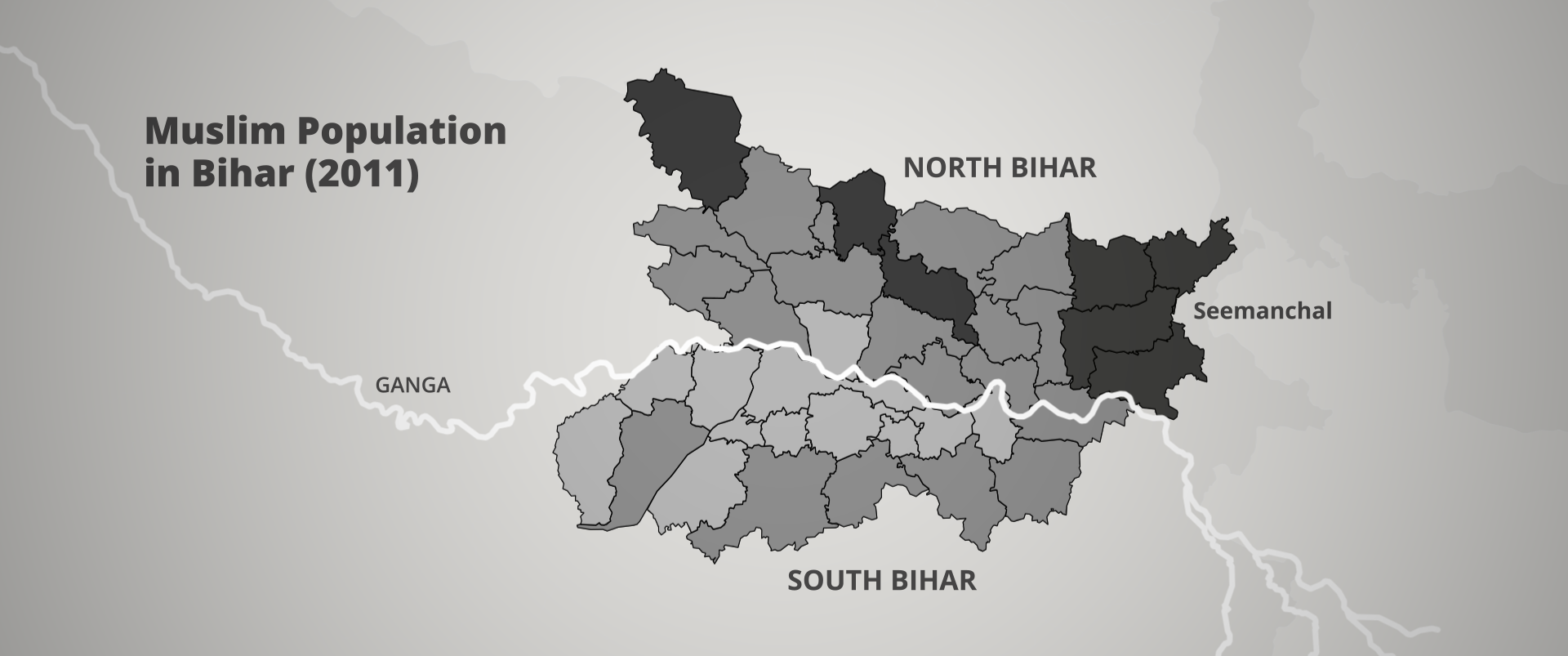

Muslims are spread across the state, but their concentration is significantly higher in North Bihar and Seemanchal. In four eastern districts — Kishanganj, Araria, Purnia, and Katihar — Muslims constitute over 35% of the population, and in Kishanganj they form a 68% majority.

Despite this demographic weight, only around 15% of Bihar’s Muslims live in urban areas. The vast majority reside in villages and small towns where access to basic services is scarce. This geographic reality directly shapes their socio-economic condition.

Education: A Foundation That Remains Weak

Education is the cornerstone of development. But Bihar’s Muslim community remains significantly disadvantaged here.

- Muslim literacy rate in Bihar (Census 2011): 56.3%

- Literacy rate for all communities in Bihar (Census 2011): 61.8%

- National average (Census 2011): 74%

Among Muslim youth (ages 15–29):

- 38.1% remain illiterate(vs. 31.7% in the rest of Bihar)

- Only 8.8% manage to complete Class 12(vs. ~15% among others)

Alarmingly, one in four Muslim students drops out before Class 10.

These figures are not just statistics — they reflect stunted opportunities, limited mobility, and lives trapped in a cycle of poverty.

Employment and Livelihoods: Hard Work, Low Recognition

Muslims constitute 17% of Bihar’s population, yet hold only around 7% of government jobs. Most work in the informal sector — labour-intensive and poorly paid, with little security or dignity.

The average monthly household income among Muslims is shockingly low:

- Rural Muslim households: ₹2,630

- Urban Muslim households: ₹3,640

With an average family size of 5–6 members, survival itself becomes a daily challenge. Many households are burdened by debt — up to 56%–57% of annual income in some areas — often taken simply to manage basic needs.

Infrastructure and Basic Services: Development Out of Reach

Basic infrastructure — roads, housing, drinking water, sanitation, and electricity — is not a privilege; it is a fundamental right. Yet, in many Muslim-majority localities, especially in Seemanchal, these essentials remain scarce or severely inadequate.

A walk through these neighbourhoods reveals the reality: broken and muddy roads, water-logged lanes, poor drainage systems, and unreliable electricity. Housing conditions are equally fragile. Nearly 80% of Muslim households live in semi-pucca or kutcha structures (NFHS-5), leaving families vulnerable to floods, storms, and seasonal hardships.

Even access to sanitation reflects this gap. In Bihar, only 71.1% of Muslim households have toilets — better than several socially backward groups in the state, yet significantly lower than the 90.3% national average for Muslims. The promise of development has simply not reached these communities.

Health Indicators: A Disturbing Reversal

Nationally, Muslim children often fare slightly better on mortality indicators than Hindu children — a phenomenon studied widely in public health research. But in Bihar, this trend reverses. NFHS-5 data shows Seemanchal districts perform among the worst in Bihar on immunisation, antenatal care, and institutional deliveries. This disparity is directly linked to low income, poor education, and weak access to public services.

Seemanchal: Marginalisation at the Border

Seemanchal lies geographically at a strategic tri-border zone touching Nepal, West Bengal, and Bangladesh. Yet despite this location — or perhaps because of it — the region suffers from:

- Severe underdevelopment

- Annual floods and land loss

- Weak infrastructure

- Scarce healthcare and schooling

- Heavy migration due to lack of jobs

Every second rural household here has at least one migrant earning outside Bihar. Floods routinely erase homes, livelihoods, and agricultural lands.

Despite massive backwardness, Seemanchal finds little mention in development policies. It comes into the national conversation only during elections or when allegations of “illegal immigrants” surface — often without evidence.

Aadhaar, SIR, and the Question of Citizenship

A significant flashpoint in recent years for Bihar’s Muslims has been the Aadhaar-related allegations and the Special Intensive Revision (SIR) of electoral rolls. What was presented as an administrative exercise became, for many residents, a moment of deep anxiety and political erasure.

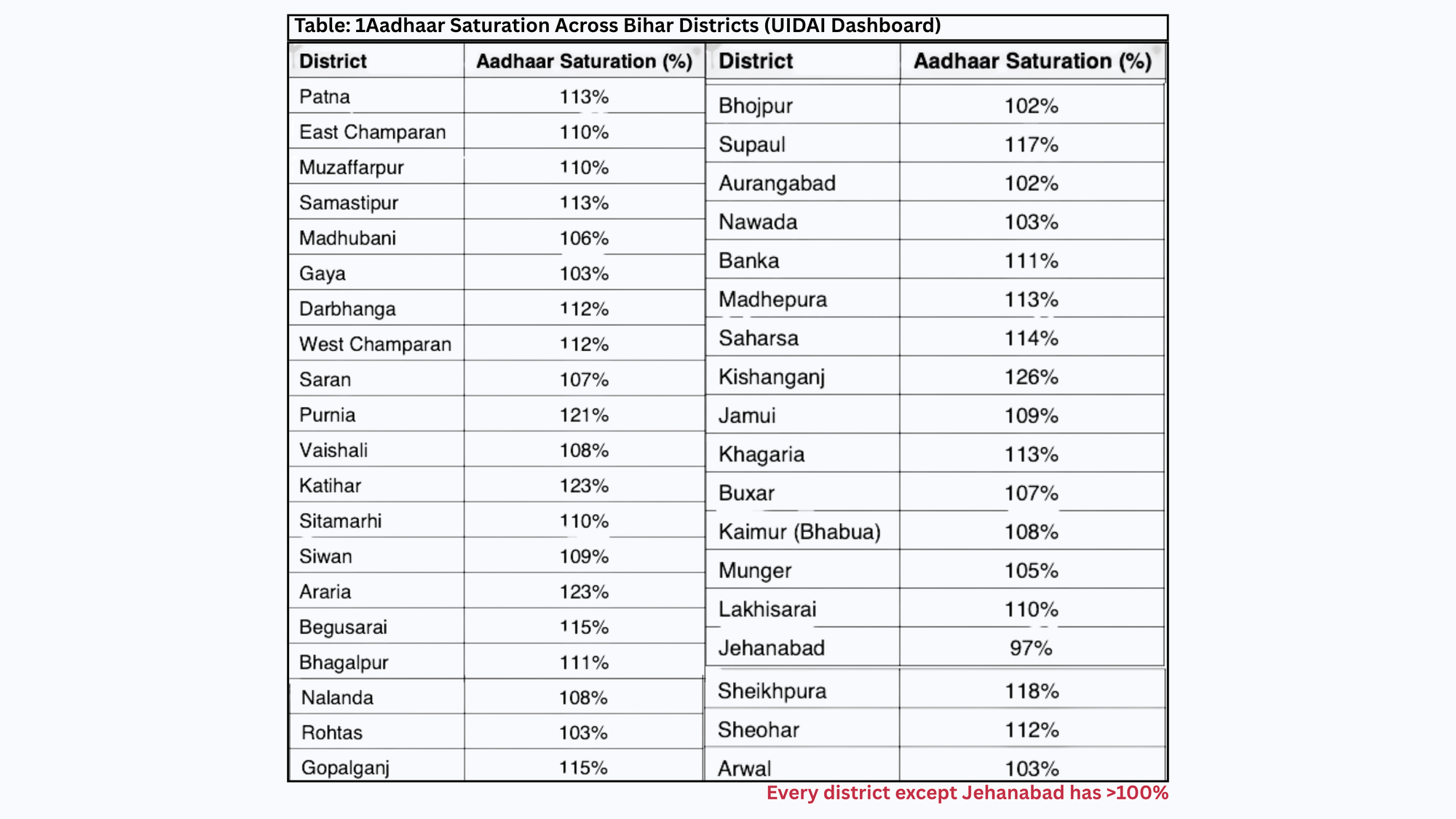

During the SIR, lakhs of voter names were reportedly deleted from lists — disproportionately from Muslim-majority districts in Seemanchal. Alongside this, a narrative of “infiltration” was amplified in political speeches and media commentary, suggesting that people from neighbouring countries had illicitly entered and registered as voters. The discourse cast suspicion not on individuals but on the entire community. However, A senior official from the Election Commission of India confirmed that during the SIR in Seemanchal not a single voter name was deleted on the ground of an alleged ‘infiltrator’.

At the same time, right-wing political leaders and sections of the media began promoting an “Aadhaar scam” theory — claiming that the number of Aadhaar cards issued in Seemanchal exceeded the population, and using this to suggest a large presence of “illegal foreigners.” This narrative was amplified as supposed proof of infiltration.

Yet, the facts tell a different story. Similar Aadhaar-population mismatches exist in several other districts of Bihar where Muslims are a tiny minority. In fact, barring Jehanabad, all 37 districts reported Aadhaar coverage above 100%. Yet none of those regions triggered political outrage or breathless media coverage. The selective alarm around Seemanchal raises an obvious question: was this truly about data, or about targeting a particular community?

Political Representation: Major Population, Minor Voice

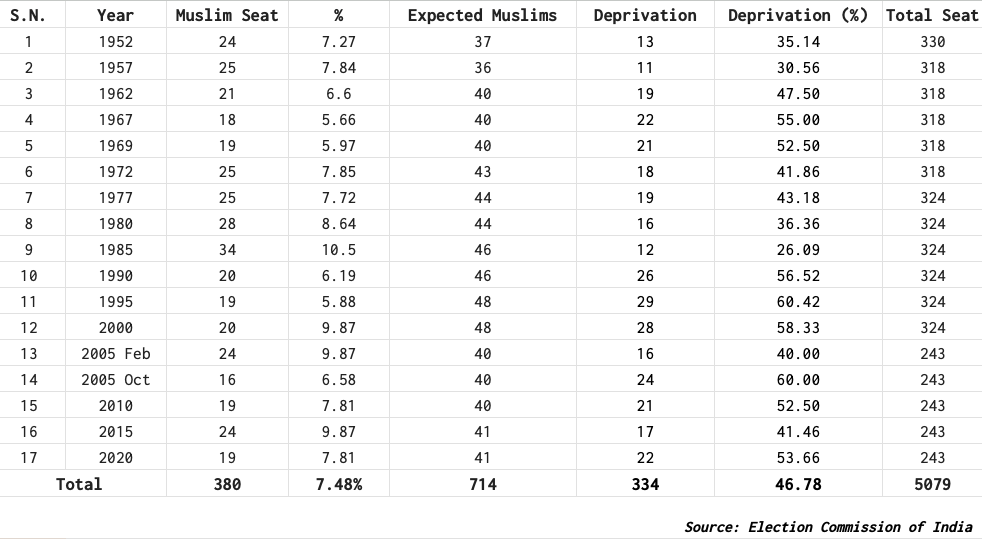

Muslims form 17% of Bihar’s population. Yet in the current assembly, they hold only 7.8% seats (19 seats). If representation matched population share, they would hold around 41 seats (Table: 1).

Across 17 state elections since 1952, only 380 Muslim MLAs have been elected out of 5,079 — just 7.5%, instead of the proportional 17% (Table: 1).

This deficit — about 335 Muslim MLAs who never made it to the assembly — is not accidental. Ticket allocation data across major “secular” parties shows that Muslim candidates consistently receive fewer seats than other groups, even where they have a strong voter presence.

The result:

- Muslims vote loyally for secular parties

- Yet receive little representation in return

- And are blamed by both sides — by the Right for “appeasement” and by secular parties for electoral defeats

It is a political paradox in which Muslims participate actively but remain structurally excluded.

Table 2: Political Representation of Muslims in Bihar (1952-2020)

Conclusion: A Community Left Behind

From education to employment, infrastructure to healthcare, welfare access to political representation — a consistent pattern emerges:

Bihar’s Muslims, especially in Seemanchal, have been made invisible in the development narrative.

They are numerically significant, culturally integral, and economically vital to the state — yet continue to be sidelined in policy, governance, and politics.

This raises urgent questions for Bihar and India:

- Why does a community forming 17% of the population have only 7% representation?

- Why are Muslims expected to help defeat majoritarian forces, yet denied political agency themselves?

- Why do development plans bypass the very regions that need them the most?

Bihar’s progress cannot be measured merely by GDP charts or election slogans. It must be judged by how it treats its most deprived citizens — and today, Bihar’s Muslims stand at the heart of that challenge.

They are not just a vote bank — they are equal stakeholders, deserving equal dignity, equal opportunity, and equal representation.

Support Independent Media That Matters

Nous Network is committed to producing bold, research-driven content that challenges dominant narratives and sparks critical thinking. Our work is powered by a small, dedicated team — and by people like you.

If you value independent storytelling and fresh perspectives, consider supporting us.

Contribute monthly or make a one-time donation.

Your support makes this work possible.