Mughals, Myths, and Modern India

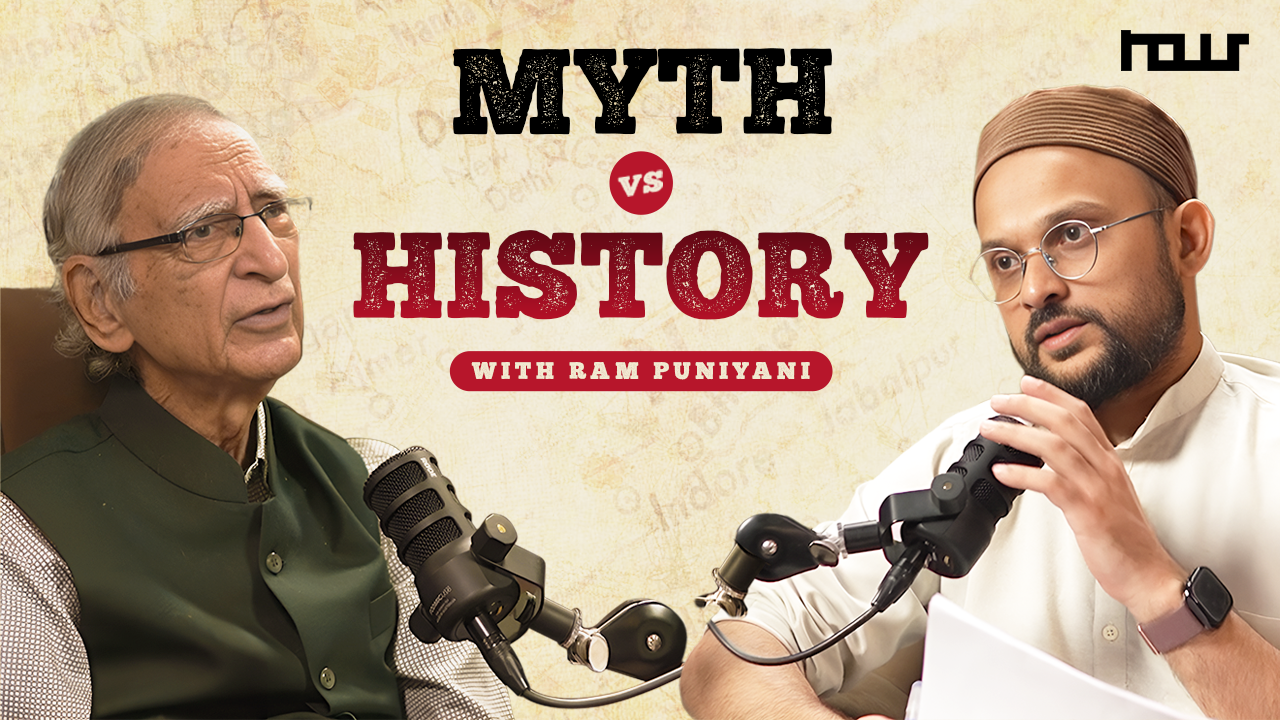

In this episode of Nous Network, we are joined by Dr. Ram Puniyani, former professor of biomedical engineering and a leading voice against communalism and the selective interpretation of history. Together, we explore how Hindutva narratives weaponise the past, from claims of temples beneath mosques to the vilification of India’s medieval rulers. Dr. Puniyani debunks myths about Mughal emperors, examines the real dynamics of battles like Akbar–Rana Pratap and Shivaji–Aurangzeb, and challenges the narrative of Islam spreading ‘by the sword.’ The conversation also traces the evolution of Indian secularism, the Emergency era, rising ethno-nationalism, and the global politics of terrorism.

Who is Ram Puniyani?

Born on August 25, 1945, into a refugee family from Jhang, Punjab (now in Pakistan), Dr. Ram Puniyani’s formative years were shaped by the upheaval of Partition and his family’s remarkable response to it. Despite being displaced to Nagpur, his devoutly religious joint family harbored “no animosity against Muslims,” with his mother maintaining close friendships with Muslim colleagues. This early exposure to pluralism amid communal tragedy profoundly influenced his worldview.

Puniyani excelled academically from childhood, winning oratory prizes and voraciously consuming books on history, politics, and social theory. He pursued a medical education (MBBS) and began teaching at Nagpur Medical College in the early 1970s, later expanding his expertise to include biomedical engineering. His scientific training would prove instrumental in developing his evidence-based approach to social critiques. In 1976, Puniyani joined IIT Bombay as a senior medical officer, eventually becoming Professor of Biomedical Engineering. During his 27-year tenure, he balanced scientific research with publishing medical monographs on Clinical Hemorheology (1996, 1998), while also growing his social engagement. However, his trajectory took a decisive turn in 1973 when he temporarily left his position at medical college to work full-time in trade union movements, immersing himself in socialist literature and workers’ rights struggles from 1973 to 1976.

The watershed moment came after the 1992 demolition of the Babri Masjid. Recognizing that communal polarization posed an existential threat to Indian democracy, Puniyani resolved to combat it systematically. By December 2004, with his family financially secure and children grown, he took voluntary retirement from IIT to dedicate himself entirely to “communal harmony” activism.

Puniyani’s signature contribution is Aman Katha (“Peace Stories”), an innovative public discourse series that transforms traditional religious storytelling formats into interactive secular dialogue. Recognizing that academic books on communalism were too theoretical for ordinary people, he adapted the familiar format of religious narratives (like Hanuman Chalisa booklets) but filled them with secular content. In Aman Katha sessions, Puniyani engages diverse audiences—workers, students, villagers—through questions about popular stereotypes: “Why do people talk about temple destructions? What happened at Partition? Why was Gandhi killed?” Rather than lecturing, he facilitates open discussions to unpack myths, making “classical narrations become interactive.” Sessions typically conclude with collective brainstorming on promoting peace, justice, and dignity across communities. This methodology has taken him to remote corners of India, making communal history accessible in local languages.

Puniyani’s worldview centers on inclusive secular democracy and opposition to communalism. He distinguishes between Indian nationalism, which treats “all people of this land” as equal citizens, and Hindu nationalism, which regards only Hindus as “original inhabitants” while treating Muslims and Christians as “aliens” with “lesser rights.” His secularism is rooted in the principle of sarva-dharma sambhava (equal respect for all religions), insisting that the state should neither interfere in religious matters nor allow religious authorities to dictate policy. He argues that Indian constitutional secularism protects all citizens rather than merely appeasing minorities, as critics often claim.

Puniyani connects caste justice with secularism, noting how communal ideology masks intra-religious hierarchies by focusing on external enemies. Drawing on historians like Bipan Chandra, he explains that communal politics treats each religious community as a separate nation while demonizing “the other,” conveniently ignoring discrimination against Dalits and women within each group.

Puniyani’s political analysis focuses intensively on Hindutva and right-wing policies. He identifies the BJP as “the electoral wing of Hindu nationalist politics,” backed by RSS ideology that organizes among Dalits and tribals through religious festivals while undermining their actual rights. He argues that current politics is dominated by “hate against minorities” as its “dominant feature.”

He distinguishes the anti-Sikh violence of 1984 (one-time revenge pogrom) from regular anti-Muslim and anti-Christian violence, describing the latter as deliberate tools of the Hindu nationalist agenda. His analysis suggests that “a section of society felt threatened” by deepening democracy and the rise of Dalits and women, leading them to “rally behind the BJP and the politics of communalism.”

Puniyani frames communal violence as organized rather than spontaneous, documenting how anti-Muslim riots follow templates (prepared lists of households, incited mobs) serving electoral goals. He has extensively analyzed events like the 2002 Gujarat riots as a “Hindu Rashtra laboratory,” demonstrating state-orchestrated violence.

Puniyani draws from multiple intellectual traditions. His early trade union activism (1973-1976) instilled left-leaning, worker-oriented perspectives through extensive reading of socialist literature. Simultaneously, he embraces Gandhian ideals of pluralism and nonviolence, frequently contrasting Gandhi’s inclusive nationalism with contemporary exclusivist Hindu nationalism. A crucial influence was Dr. Asghar Ali Engineer, the late Muslim secularist whose studies on communalism were “a great source of shaping his understanding” of Indian history and sectarianism. Puniyani also incorporates Ambedkarite calls for social justice, evident in works like “Quest for Social Justice.”

His scientific background is evident in his emphasis on evidence-based arguments, which utilize official data to refute popular myths. While not explicitly labeling himself “Marxist” or “Gandhian,” his worldview represents a synthesis of Gandhian pluralism and socialist egalitarianism, grounded in secular humanism and rationalist methodology.

Puniyani maintains an active public presence through lectures, workshops, and media engagement across India. He regularly speaks at universities, workers’ forums, and community gatherings on themes including threats to democracy, communal politics, minority myths, and terrorism. His essays appear in various Indian media outlets, and he edits the fortnightly e-bulletin “Issues in Secular Politics.”

Adapting to modern communication, he maintains a popular YouTube channel (DrRamPuniyani) featuring talks on rationalism and anti-Hindutva themes, despite facing threats from fringe elements. His graphic books and accessible materials aim to deconstruct Hindu-right myths about medieval temple destruction, Muslim demography, and other contentious topics.

At nearly 80, Puniyani continues to travel across India, conducting Aman Katha sessions, embodying his commitment to secular democracy. His work provides a comprehensive framework for understanding how communal politics operates, why it threatens democratic values, and how secular forces can counter its divisive agenda. His consistent argument that communalism is fundamentally anti-democratic and that religious identity is manipulated for political power remains highly relevant in contemporary Indian politics.

Through his unique blend of scientific rationalism, grassroots engagement, and ideological clarity, Ram Puniyani represents a distinctive voice in India’s secular democratic discourse, bridging academic analysis with popular education to promote inclusive nationalism and social justice.

The Politics of Temples Under Mosques

Hindutva ideologues frequently claim that many old mosques were built atop destroyed Hindu temples (e.g., Babri Masjid, Gyanvapi, etc.). These assertions, often unsupported by evidence, are used to invoke a sense of “civilisational injustice” and to mobilise public sentiment. Ram Puniyani points out that recent mosque-to-temple claims have been “made-up” controversies. Even RSS chief Mohan Bhagwat cautioned against assuming a Shivling under every mosque. Nevertheless, organisations like the VHP and Organiser (RSS’s mouthpiece) celebrate “temple restorations” as quests for Hindu identity and “civilisational justice.”

The Supreme Court has noted that Babri Masjid’s construction did not legally involve temple demolition, and that the 1949 idol placement in Babri was illegal; it called the 1992 demolition an “egregious violation of the rule of law.” Despite this, the BJP/VHP pushed forward the Ram Temple project by prioritizing faith over legal title, and the central government even formed a trust to oversee the construction.

Puniyani, whose activism was galvanised by the Babri demolition (“I felt the communal issue is out to erase democracy”), emphasizes that impunity for Babri’s destruction sent a dangerous signal. He notes that all the accused in the demolition received a “not guilty” verdict, and the presiding judge later got a plum job. This lack of accountability, he argues, emboldened further vigilante violence (cow-vigilante lynchings, “love-jihad” raids, attacks on Christians, etc.), demonstrating that perpetrators “know they can get away with their illegal acts.”

Puniyani also criticises how mainstream discourse is recasting history to suit present politics. He warns that a “Hindu first” version of the past is being taught in schools and media, not based on objective evidence, but on current ideological needs. In his view, this is akin to the way Pakistan’s schoolbooks erase entire minorities; RSS thinkers like Golwalkar explicitly drew on Nazi racial ideas to define India as an inherently “Hindu nation.” These distortions ignore India’s plural heritage and serve to justify contemporary communal agendas.

Puniyani’s work on this theme underscores that “temples under mosques” claims are less about archaeology and more about politics. He repeatedly debunks these myths in talks and writings, demonstrating that even respected historians have found no evidence of a vast network of destroyed temples.

Vilification of Muslim Rulers

A cornerstone of Hindutva ideology has been the portrayal of medieval Muslim rulers as villains who “destroyed thousands of temples” and forced conversions, creating a binary Hindu-Muslim history. Ram Puniyani systematically busts these legends. He notes that real historians long ago debunked the idea of mass temple demolition or conversion by sword. Most destruction was opportunistic loot, and many Muslim emperors patronised temples as well. For example, Ghazni’s armies included Hindu generals, and Emperor Aurangzeb both demolished some temples and granted land for others. Virtually every purportedly “Hindu” king had Muslim allies or officers (Rana Pratap’s top general, Hakim Khan Sur, was Muslim; Shivaji’s principal secretary was Maulana Haider Ali, and his army had many Muslims). These facts undermine the communal narrative that history’s only “Hindu–Muslim” battles were holy wars; they were power struggles typical of all pre-modern empires.

Puniyani highlights how the public discourse on history is often a legacy of colonialism. He cites the common Hindutva refrain: “villainous foreigners (Muslim kings) attacked India, spread Islam, destroyed temples.” But credible scholarship tells a different story. Puniyani points out, for instance, that Raja Mansingh (a Hindu king) fought for Akbar. In contrast, Hakim Khan Sur (a Muslim general) fought for Rana Pratap, showing the communities were not neatly divided by religion. Likewise, mass conversions to Islam often came from people (especially lower-caste Hindus) seeking escape from the caste system, as even Swami Vivekananda acknowledged.

Why do BJP/RSS leaders push these narratives? Puniyani argues they serve to mobilise Hindu identity and justify current agendas. For example, he notes that the RSS-affiliated Organiser openly calls temple reconstruction a quest for “our identity” and “civilisational justice.” By contrast, scholars like Romila Thapar or Richard Eaton, whom Puniyani references, have found little historical support for widespread temple destruction or large-scale violent conversion. Puniyani often takes these scholarly insights into the field via his “Aman Katha” talks, directly addressing questions about temple destructions, forced conversions, and royal atrocities. In doing so, he emphasizes that history has been twisted, and communal myths are being sold for political gain.

To promote communal harmony, Puniyani stresses India’s syncretic past. He reminds audiences (as he did in Patna in 2015) that Islamic and Hindu traditions have richly interacted, with Sufi and Bhakti saints blending their faiths. Even the author of the Ramcharitmanas (Tulsidas) famously called himself “a slave of Ram who lives in a mosque,” yet today hardliners seek to demolish mosques in Ram’s name. By highlighting such ironies, Puniyani encourages Indians to see beyond one-sided narratives.

From the Emergency to Today - Hindu Nationalism and Authoritarianism

Ram Puniyani contrasts the 1975–77 Emergency under Indira Gandhi with the rise of contemporary Hindu nationalism. He acknowledges that the Emergency was a terrible blow to India’s democracy—civil liberties were suspended and opponents jailed—but he distinguishes dictatorship from fascism. As he explains, many kinds of authoritarian rule exist, but fascism has specific traits (mass mobilisation through elections, corporate backing, expansionist aims, and systematic targeting of an “enemy” group). By this definition, Indira’s regime was an authoritarian dictatorship, not a fascist regime. (He notes, for example, that unlike Nazi Germany, India never set up concentration camps or actively aimed at territorial conquest in the 1970s.)

In Puniyani’s view, the RSS/Hindutva project more closely matches fascism’s profile. He points out how early RSS leader M.S. Golwalkar explicitly drew on Nazi racial ideas to define India as a “Hindu Rashtra” and to claim that non-Hindus must subordinate themselves. Today’s Hindutva politics, he argues, is marked by ultra-nationalism and a continual construction of the “other” (Muslim or Christian) as a threat. For example, he describes the RSS ideology as “the Indian incarnate of Fascism”: it promotes Akhand Bharat (an expansionist Greater India), worships a single religious-national symbol (the saffron flag/Bharat Mata), and demands loyalty to a Hindu identity above constitutional patriotism.

Even Gandhi observed long ago that Hindu communalism, in its purist form, had fascist potential – a warning that Puniyani sees as coming true in some modern rhetoric. A key debate today is whether slogans like “Bharat Mata ki Jai” or Vande Mataram express secular patriotism or exclusive nationalism. Puniyani argues Hindu nationalists have co-opted them into a militant vision. He cites leaders (including ex-PM Manmohan Singh) who say this slogan is being used to create “a purely emotional idea of India that excludes millions of residents and citizens.” In practice, forcing one religious symbol (a goddess-like Bharat Mata carrying a saffron flag) at official events can marginalise others.

Puniyani contrasts this with India’s constitutional pluralism: as Kerala’s Education Minister put it, “Indian nationalism is not founded on a single cultural image, but on the inclusive and democratic vision enshrined in our Constitution.” He stresses that true patriotism, as Gandhi and Nehru saw it, is secular and inclusive of all communities.

Finally, Puniyani warns that pushing for a “Hindu Rashtra” or equating national loyalty with Hindu religious symbols threatens India’s diversity. It risks reducing citizens of other faiths to second-class status (echoing Golwalkar’s dicta). This ideological narrowing can breed resentment and even violence. In his book Communalism, Terrorism and Social Perceptions, he discusses how communal stereotyping can slide into justifying extremism. In short, there is a thin line between communal hatred and organized violence: once a community is dehumanized in political rhetoric, fringe actors may feel justified in terrorism or vigilantism.

References

- https://youtu.be/xCw2Aiepirk

- https://youtu.be/VE7KMoe6Wvg

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=N09jCF26QjU&t=2688s

- https://www.youtube.com/@DrRamPuniyani

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qG1rpTXJv8A&pp=ygUMcmFtIHB1bml5YW5p

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z7SavJJaja0&pp=ygUMcmFtIHB1bml5YW5p

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1edeMLbdHdw&pp=ygUMcmFtIHB1bml5YW5p

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KJoVK4H2fv4&pp=ygUMcmFtIHB1bml5YW5p

- https://countercurrents.org/2016/11/what-do-we-know-about-ram-puniyani-and-his-aman-katha/

- https://archive.siasat.com/news/rewriting-history-and-sectarian-nationalism-1334532/

- https://www.countercurrents.org/comm-puniyani100306.htm

- https://muslimmirror.com/communal-violence-bases-on-myths-ram-puniyani/

- https://hastakshep.com/symptoms-of-fascism

- https://www.indiancurrents.org/article-bharat-mata-controversy-yet-again-ram-puniyani-2645.php

Support Independent Media That Matters

Nous Network is committed to producing bold, research-driven content that challenges dominant narratives and sparks critical thinking. Our work is powered by a small, dedicated team — and by people like you.

If you value independent storytelling and fresh perspectives, consider supporting us.

Contribute monthly or make a one-time donation.

Your support makes this work possible.