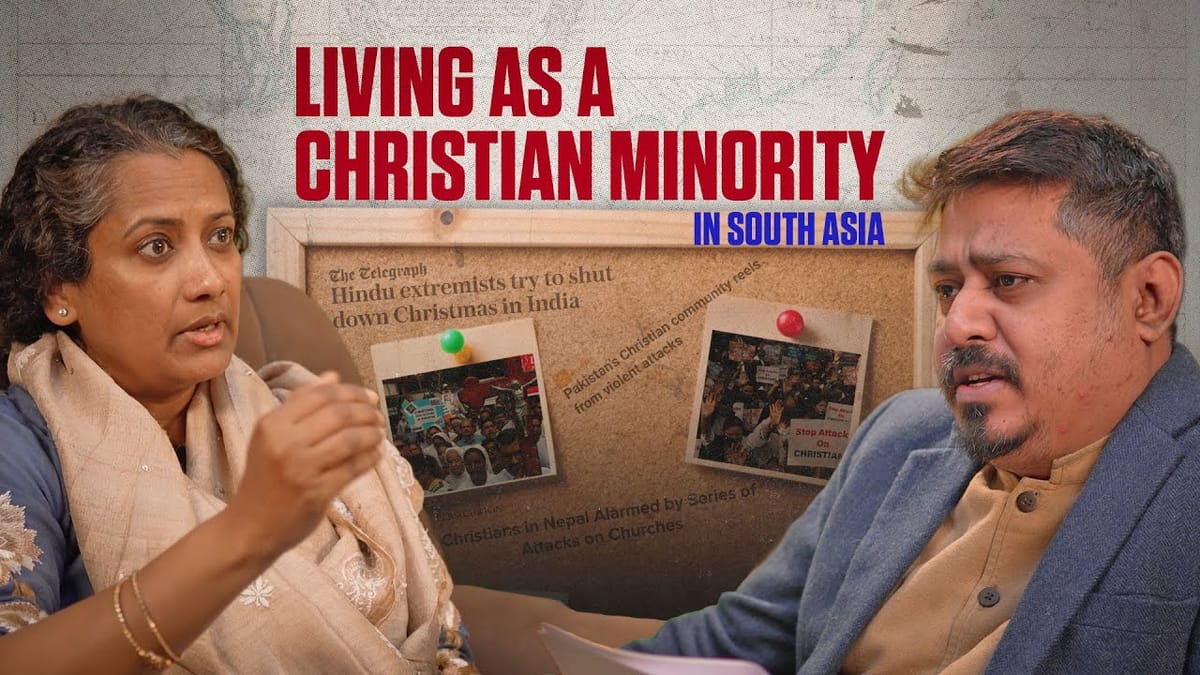

How Law and Impunity Shape Christian Minority Life in South Asia | Tehmina Arora Explains

Narratives around religious conversion are reshaping laws, policing, and daily life for minorities across South Asia. From legal harassment to mob violence, this discussion highlights regional patterns raising urgent questions about religious freedom and state accountability.

The Architecture of Impunity: How Law and Narrative Shape Christian Minority Life in South Asia

Across South Asia, Christian minorities are increasingly living under conditions of fear, suspicion, and legal uncertainty. Narratives of “forced” or “induced” religious conversion have travelled seamlessly across borders, shaping similar laws, policing practices, and patterns of violence—from India and Pakistan to Bangladesh and Nepal. What appears as isolated local conflict is, in reality, part of a wider regional pattern.

In a recent conversation on the nous network, journalist Asad Ashraf speaks with Tehmina Arora, human rights advocate and Chief of Public Advocacy at the United Christian Forum (India), to examine how these narratives translate into everyday consequences—from prayer meetings treated as criminal acts to mob violence operating with near-total impunity.

Criminalising Faith: The “Forced Conversion” Narrative

At the centre of this crisis lies a powerful and persistent allegation: that Christians are engaged in “fraudulent” or “forced” conversions. This narrative reframes the constitutional right to freedom of conscience as a demographic threat, often portraying Christians as agents of foreign influence.

The result is the criminalisation of ordinary life. As Arora notes, “Constantly having to prove that we are not converting anyone—that we are simply praying in our own homes—has become the norm.” Under this logic, the definition of “conversion activity” has expanded dangerously to include:

- Private gatherings, including birthday parties or weddings, raided by police

- Charitable work, such as children’s homes or medical camps, treated as suspect

- Routine domestic life, where even religious music heard by a neighbour or delivery worker can trigger a police complaint

In Nepal, for instance, running a children’s home without specific approvals can legally be interpreted as inducement to convert, regardless of intent or evidence.

Law as a Shield for Violence

Perhaps the most disturbing aspect Arora highlights is the collusion between mobs and law enforcement. The forced-conversion narrative grants vigilante groups a sense of legitimacy, while police action often targets victims rather than perpetrators.

“The routine pattern is this,” Arora explains. “A mob arrives, beats you up in your own home or church—and the complaint is registered against you.”

Data from the United Christian Forum illustrates this impunity starkly. Of nearly 840 incidents of violence against Christians in India in a single year, formal police complaints were registered in only around 40 cases. Fear of retaliation, counter-cases, and further violence keeps many victims silent.

This pattern was explicitly acknowledged by the Supreme Court of India in the Fatehpur judgment, which criticised police for filing “copy-paste” FIRs—sometimes duplicating grammatical errors and even naming minors or deceased individuals—revealing a systematic effort to harass rather than protect.

Parallel Systems of Oppression

While legal frameworks differ across countries, their misuse follows strikingly similar patterns. Pakistan’s blasphemy laws and India and Nepal’s anti-conversion laws operate through the same mechanisms:

- Settling personal or economic disputes under the cover of religious offence

- Third-party complaints, allowing unrelated individuals to initiate criminal cases

- Process as punishment, where years of detention, legal battles, and social boycott occur even when acquittals are likely

The law itself becomes a tool of intimidation.

Intersection of Caste, Gender, and Economy

The impact of this violence is deeply intersectional.

- Caste discrimination remains institutionalised. In India, the 1950 Presidential Order denies Scheduled Caste status to Dalits who convert to Christianity or Islam—despite official recognition that social discrimination persists regardless of religion. Arora calls this “the real anti-conversion law.”

- Women and girls face distinct vulnerabilities. In Pakistan, minority girls are targeted for abduction and forced marriage. In conflict zones such as Manipur or parts of Chhattisgarh, women endure sexual violence and public humiliation as tools of collective punishment.

- Economic rivalry also fuels attacks. Successful Christian schools, tuition centres, or welfare initiatives are often targeted by competitors using conversion allegations to shut them down. Laws like India’s FCRA further restrict civil society, harming education and healthcare for the poorest communities.

Administrative Erasure: Denial of Dignity in Death

Beyond physical violence lies a quieter, bureaucratic form of persecution. Across parts of India, Nepal, and Sri Lanka, Christians are increasingly denied burial rights. Families are forced to transport bodies long distances, bury their dead in forests, or face the trauma of exhumation.

“It is a profoundly dehumanising process,” Arora observes, “especially at a time of grief.”

International Pressure and Selective Accountability

The conversation also highlights differing geopolitical responses to human rights scrutiny.

Pakistan, dependent on international trade mechanisms such as the EU’s GSP+, has shown limited responsiveness—recently raising the legal marriage age to address forced conversions of minors. India, by contrast, benefits from its image as a strategic and economic power, allowing it to deflect international criticism of its religious freedom record more easily.

Conclusion

The persecution of Christians in South Asia is not accidental nor episodic. It is the outcome of a deliberate convergence of narrative building, legal weaponisation, and administrative indifference.

As Arora argues, genuine religious freedom is not a peripheral concern—it is essential to social stability, constitutional integrity, and global credibility. Until states confront this reality, civil society remains the last line of defence, documenting abuse and building solidarity across faiths.

As she asks pointedly: “We change our political ideas. We change our relationships. Why, then, must religious belief alone be treated as a crime?”

Support Independent Media That Matters

Nous is committed to producing bold, research-driven content that challenges dominant narratives and sparks critical thinking. Our work is powered by a small, dedicated team — and by people like you.

If you value independent storytelling and fresh perspectives, consider supporting us.

Contribute monthly or make a one-time donation.

Your support makes this work possible.